Can you tell me more about spirituality and reverence among atheists?Cath asked this in the comments of my previous post, in response to my comment about religious people failing to see the deep spirituality of Dawkins. I'll get to Dawkins shortly. I want to start with a note on definitions.

I am an atheist, but all that says is that I suspect there is no supernatural creator or moral lawgiver in the universe. It says nothing about my spirituality.

I am an atheist, but all that says is that I suspect there is no supernatural creator or moral lawgiver in the universe. It says nothing about my spirituality.

My worldview, the basis of my ethical and spiritual approach to the world, is Humanism. My favorite sound-bite definition is that offered on the Humanist Network News podcast - that Humanism is a non-religious worldview based on reason and compassion. For more depth, Wikipedia gives a good overview of Humanism.

First, you may have noticed from past posts

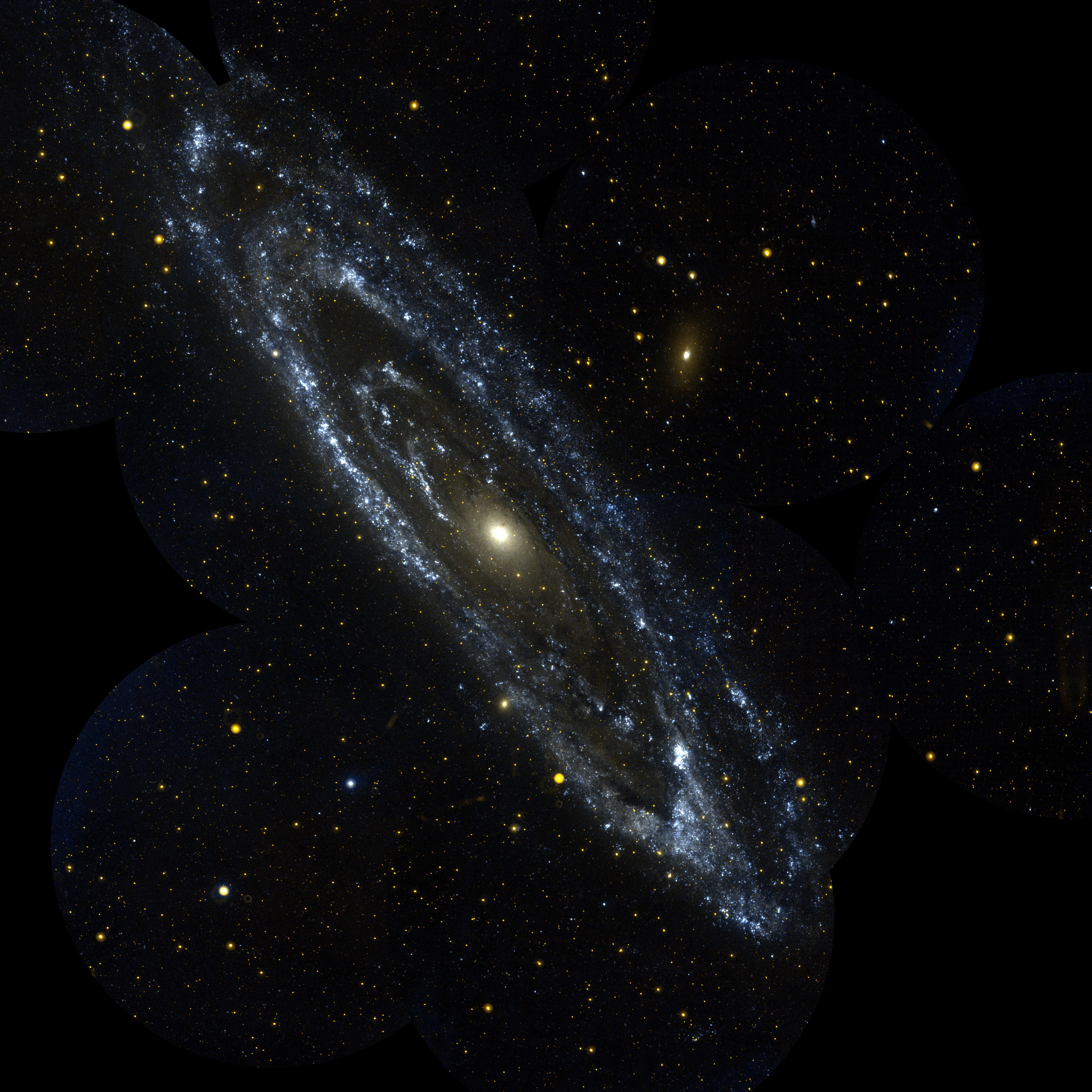

that I'm interested in Carl Sagan's analogy of the Cosmic Calendar to illustrate the depth of cosmic history. I find it enthralling that the universe is almost unimaginably old. The knowledge of how truly vast time and space are fills me with reverence for the universe. Though it has no mind, though it has no consciousness of me as an individual, nevertheless it is a thing of awesome beauty, and it is a recurring source of joy to remember that, through no merit of my own, I am lucky enough to be part of it.

that I'm interested in Carl Sagan's analogy of the Cosmic Calendar to illustrate the depth of cosmic history. I find it enthralling that the universe is almost unimaginably old. The knowledge of how truly vast time and space are fills me with reverence for the universe. Though it has no mind, though it has no consciousness of me as an individual, nevertheless it is a thing of awesome beauty, and it is a recurring source of joy to remember that, through no merit of my own, I am lucky enough to be part of it.That sense of staggering good fortune is touchingly expressed at the start of Richard Dawkins' book Unweaving the Rainbow:

We are going to die, and that makes us the lucky ones. Most people are never going to die because they are never going to be born. The potential people who could have been here in my place but who will in fact never see the light of day outnumber the sand grains of Sahara. Certainly those unborn ghosts include greater poets than Keats, scientists greater than Newton. We know this because the set of possible people allowed by our DNA so massively outnumbers the set of actual people. In the teeth of these stupefying odds it is you and I, in our ordinariness, that are here.Now I'd like to share with you a bit about my wedding with Deena seven years ago. It was before we had discovered Humanism as an organized community, but we already held broadly humanist beliefs, and the symbolism we chose then still resonates with us today.

The ceremony was held outdoors, in a cathedral of trees, with a small brook flowing by. Charles Darwin and his intellectual successors have shown us how truly connected we are to all of life - we are cousins to the ants and the poplar trees and the magpies.

We had friends and family with us. Marriage is a human act, and the moral community in which we made our commitment consists entirely of ourselves and other humans.

The poem "Habitation" by Canadian writer Margaret Atwood was read:

Marriage is notOur spirituality is provisional and fragile. It is provisional in that the things that matter to us, the people and life choices, could have been otherwise. I was not destined to meet Deena; I simply did meet her. Chance got us that far;

a house, or even a tent

It is before that, and colder:

the edge of the forest, the edge

of the desert

the unpainted stairs

at the back, where we squat

outdoors, eating popcorn

the edge of the receding glacier

where painfully and with wonder

at having survived even

this far

we are learning to make fire.

our own choices (and further chances) have taken us to where we are today. The fortune we cherish is fragile because there are so many things that could shatter it, that could have made it other than what it is.

our own choices (and further chances) have taken us to where we are today. The fortune we cherish is fragile because there are so many things that could shatter it, that could have made it other than what it is.One guest at our wedding said that the above poem was rather cold. But it mirrors the sentiment from the Dawkins passage (which we wouldn't read for another six years). Our wealth lies not in having a pleasant ultimate destiny, but in random undeserved strokes of fortune, and our own capacity to react well to them.

Not every event has an actor behind it. There are no guarantees that justice will prevail. As conscious, moral beings, we are the only force in the universe that can push the balance toward good. Therein lies the starkness that can horrify the existentialist, but also the responsibility that motivates us as humanists.

We ate a symbolic meal during the ceremony, exchanging pinches of granola and toasting each other with our favorite drinks - fizzy apple juice for Deena, chocolate milk for me. We build our connections to other humans through a myriad of everyday acts - like the act of eating a meal together.

A gust of wind spilled most of the drinks over the little table we were using, and our wedding certificate still bears the brown stain of the chocolate milk. There was still enough left for the toast. We love telling friends where the brown stain on the wedding certificate came from.

The table was from the house of my granny, who had recently died. Though we do not believe people's souls survive after death, we cannot deny that memories of a person live on in others. We honour the memory of dead loved ones, and hope to live well so that the memories we leave in others after we die will be good ones.

The wedding was at noon, followed by a picnic lunch for all one hundred guests. Through the afternoon we walked about and played games. There was an inflatable bouncy castle on the lawn, frisbee golf all around, a treasure hunt, and general merriment.

At the evening meal, we had dessert first. Sometimes, the point is to enjoy life, not to postpone enjoyment.

At the evening meal, we had dessert first. Sometimes, the point is to enjoy life, not to postpone enjoyment.We (Deena and I) tend to look at life, spirituality, and ethics as the ancient Greeks did. Spirituality and ethics are not confined to when a person prays, or meditates, or is performing certain acts. They permeate our entire life - sometimes at a conscious level, sometimes not.

I hope that has at least started to answer your question, Cath.

I've never been confortable with the word spirituality - reverence, awe or respect serve the same purpose, but without the suggestion of the supernatural.

ReplyDeleteWhen I watch an intense lightening storm I'm in awe of its power and beauty, the way it makes me aware of just how overwhelming nature can be. And it's the same when contemplating the sheer power of mutation and natural selection. But I wouldn't describe such feelings as spiritual in any way.

Matt,

ReplyDeleteI tend to think of "spirituality" in the sense that Richard Norman uses it in his book On Humanism. It's parallel to the sense of the word "spirit" in the phrase "things that lift the spirit".

I understand and sympathize with your feelings - religious uses have pervaded our language for so long that it's difficult to disconnect words like "spirituality" from the supernatural.

But the human side of what is meant by such words (there are others, such as "sacred" and "soul") is important even to non-religious people, and if we discard any word that has a religious association, we risk cutting ourselves off from communicating the important, real human elements of those meanings.

We don't allow religious zealots to get away with appropriating words like "values" and "family" for their own narrow uses. Humanists have values. Humanist value family. Similarly, humanists have the subjective experience of spirituality; we simply interpret it in a non-religious way.

I think words like "value", which can have quite a precise meaning, are different to more nebulous ones such as "spirit" or "soul" - and when it comes to the latter I think we have better words which more accurately capture the meaning of what we're trying to describe.

ReplyDeleteIt might make conveying things to the more religious-inclinded trickier, but I just wouldn't feel comfortable using words that are generally used to describe something quite different in nature.

I was first introduced to the idea of "atheistic spirituality" by one of our local outspoken atheists. Infamous guy. In a town that gets as close to a "bible belt" that South Africa has. (At least most churches have trained theologians.) He studied psychology.

ReplyDeleteHe introduced me to the idea when we were talking about studies showing "theists are happier beings". He responded with the idea that maybe people with a developed "spirituality" are happier beings, and that maybe some studies should be done that took "spiritual atheists" into consideration. I suspect many scientists would fall into this category, I'm echoing Carl Sagan: I think he said something like "science can be a great source of spirituality".

Yea, words. Personally, I feel theism has had a long time to develop some good words to describe a particular aspect of humanity. As a post-theist, I'd embrace these words.

Arthur C Clarke had the word "God" banned in The Final Odyssey (3001), but it was replaced by another word, because they found they still needed a word. How naive am I to think we could get there without actually having to replace the word?

BTW, Dawkins still uses "God", from http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/faith/article1767506.ece:

I ask him what words he uses when he swears. The same as everyone else, he says. For example, “O God help us” when he gets a dreadful essay from a student. Does he ever think then that he’s invoking God? “No, it’s part of a language so it doesn’t really matter what the word means.”

Not that I consider Dawkins an authority on where we should go with language and what we should do about religion. ;)

For some reason my browser's been messing up and since Hogmanay the last post of yours I've been able to see was "Flowers and the end of the year". I assumed you were too busy getting ready for Canada to post.

ReplyDeleteThen today I logged in, and found plenty of deep, well thought through, and positive posts such as this one, and I'm comparing it with my own; narrow and antagonistic as they are.

I loved the poem by M. Atwood. very nice.

ReplyDelete